Axel Vervoordt's Timeless Designs Embrace Imperfection and History

Axel Vervoordt's approach to interior design goes far beyond decoration. His spaces emerge from time, judgment, and a deep respect for materials—whether aged, raw, or patinated. For decades, he has treated imperfection and history not as flaws but as essential elements of his work.

His influence stretches from his 16th-century Belgian castle to Seoul's Roden Museum, where natural textures and antique objects define his signature style.

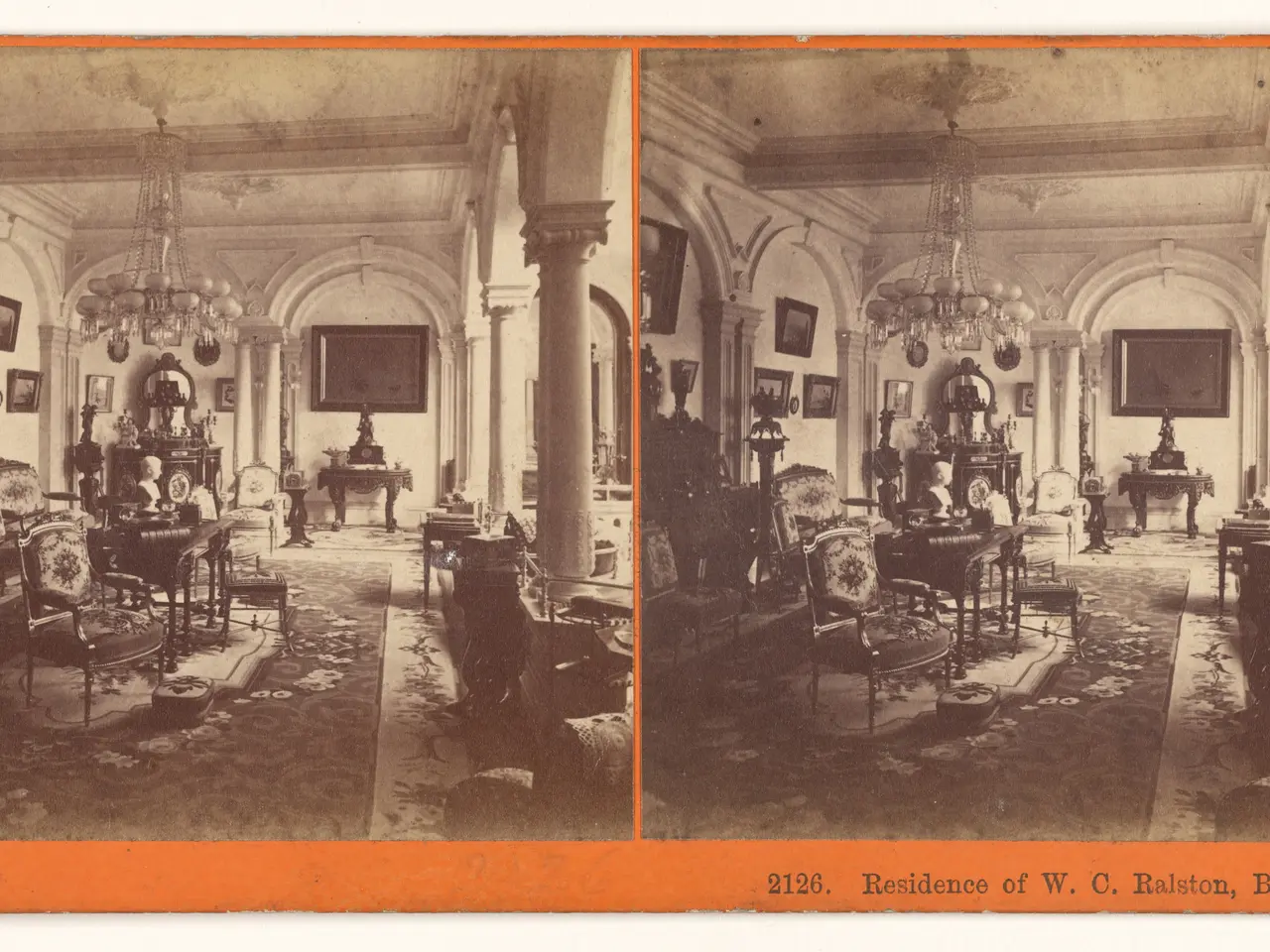

Vervoordt's design philosophy took root in his teenage years. Growing up in Belgium, he collected stones, fossils, and weathered objects, drawn to their natural patina. This early fascination with wabi-sabi—the beauty of impermanence—later shaped his career. His own home, Kasteel van 's-Gravenwezel, reflects this: exposed stone walls, ancient beams, and minimalist furniture create a dialogue between past and present.

His process relies on patience, not speed. Materials age, surfaces wear, and objects accumulate meaning over time. He treats these changes as collaborators, not obstacles. A 17th-century trunk might sit beside a modern abstract piece, each valued for its craftsmanship and story. This layered approach avoids novelty in favour of depth.

Projects like the Roden Museum in Seoul demonstrate his method. There, aged limestone, raw concrete, and antique Korean ceramics form serene, textured spaces. His rooms feel curated rather than decorated, shaped by years of observation and restraint. This quiet confidence allows him to refuse compromises that might dilute his vision.

Vervoordt's influence extends beyond his own work. Belgian minimalism—marked by pale plaster, low-slung furniture, and antique surfaces—owes much to his principles. He values material culture over fleeting trends, letting objects speak for themselves. His designs predict how a space will evolve, not just how it will look on completion.

Vervoordt's interiors endure because they embrace time as a creative force. His spaces grow richer with age, use, and careful editing. By treating imperfection as intention, he redefines how design can honour both history and modern life. The result is not decoration, but a translation of living into space.